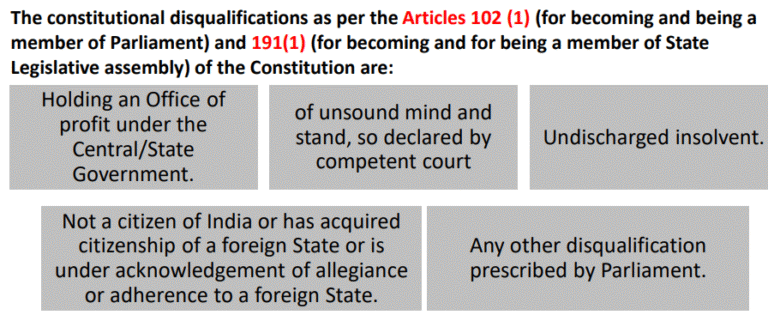

The Supreme Court has urged Parliament to review the role of Assembly Speakers and Chairmen in deciding disqualification cases under the Anti-Defection Law, citing delays and possible bias, and directed the Telangana Speaker to resolve pending petitions against 10 BRS MLAs who defected to the Congress in 2024.

Background

- Phrase origin: “Aaya Ram Gaya Ram” became famous in 1967 when a Haryana MLA changed parties thrice in one day.

- Law introduction: The Tenth Schedule was added through the 52nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1985 to control political defections.

Grounds for Disqualification

- A legislator from a political party can be disqualified if they:

- Voluntarily give up party membership.

- Vote or abstain from voting against the party’s direction without permission.

- Exemptions:

- Prior party permission.

- Party condonation within 15 days of the act.

- Independent members: Disqualified if they join a political party after election.

- Nominated members: Disqualified if they join a political party after six months of nomination.

- Decision-making authority: Speaker/Chairman of the House.

Exceptions

- Original law had:

- Split by one-third members (removed in 2003 to strengthen law).

- Merger approved by at least two-thirds members of the legislature party.

Important Supreme Court Judgments

- Kihoto Hollohan v. Zachillhu (1992) – Speaker’s decision is subject to judicial review by High Courts and the Supreme Court.

- Keisham Meghachandra Singh v. Speaker, Manipur (2020) – Set a three-month limit for deciding disqualification cases.

Issues and Challenges

- Delays: No strict timeline for Speaker’s decision, enabling prolonged cases.

- Bias: Speaker is usually a ruling party member, raising impartiality concerns.

- Legislative autonomy vs. judicial intervention: Courts reluctant to interfere early.

- Freedom of speech: Law limits legislators’ ability to dissent within the party.

- Rigid whip system: Discourages internal party debate.

Way Forward

- Shift disqualification power to independent bodies or Election Commission to ensure neutrality.

- Set mandatory timelines for deciding cases.

- Reform whip system to allow greater debate on non-confidence or non-money bills.

- Promote internal party democracy to balance discipline with freedom of expression.

Representation of the People Act, 1951

- Offences like promoting enmity, bribery, electoral fraud.

- Offences like hoarding, adulteration, dowry crimes.

- Conviction of two years or more = disqualification during sentence + 6 years after release.

- Section 8(4) (three-month appeal window) struck down in Lily Thomas v. Union of India (2013), making disqualification immediate upon conviction.

Conclusion:

While the Anti-Defection Law has curbed opportunistic political defections, loopholes and delays in its enforcement weaken its purpose. A reformed framework with independent adjudication, fixed timelines, and greater space for intra-party debate is essential to protect both political stability and democratic freedom in India’s legislative process.