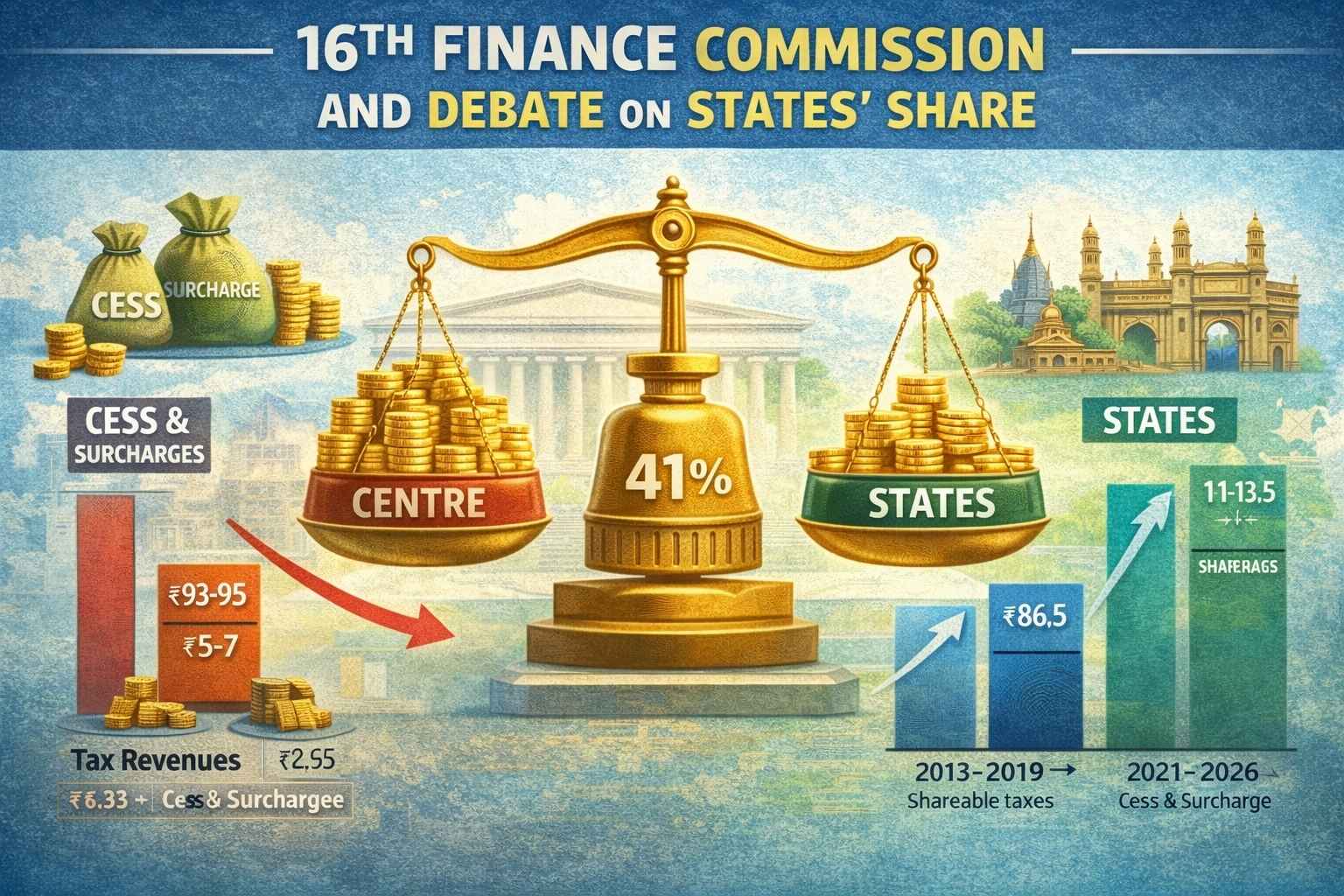

The 16th Finance Commission (FC) has retained the States’ share in vertical devolution at 41%, despite a rare consensus among States demanding an increase. The issue is significant for aspirants preparing Indian Economy and Polity through IAS coaching in Hyderabad, as it directly concerns fiscal federalism.

Background

The Finance Commission recommends how tax revenues are shared between the Centre and States.

The 16th FC kept the vertical devolution rate at 41%, the same as the 15th FC.

However, the divisible pool excludes cesses, surcharges, and collection costs, which are rising sharply, reducing the effective share available to States. This debate is frequently discussed in UPSC online coaching classes under Centre–State financial relations.

Shrinking Divisible Pool

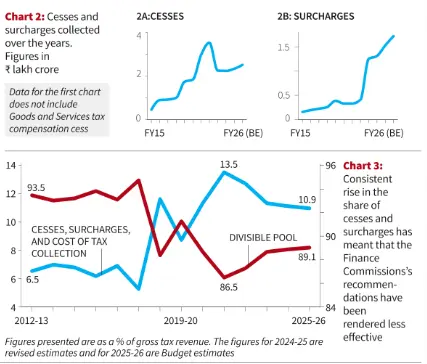

- Between 2013–2019, for every ₹100 collected, ₹93–95 came from shareable taxes; only ₹5–7 from cesses/surcharges.

- By 2021–22, shareable taxes fell to ₹86.5, while cesses/surcharges rose to ₹13.5.

- In FY26, projections show ₹89 from taxes and ₹11 from cesses/surcharges.

- Collections of cesses rose from ₹44,688 crore (FY15) to ₹3.52 lakh crore (FY22); surcharges rose from ₹15,702 crore (FY15) to ₹1.72 lakh crore (FY26 expected).

- This means the divisible pool’s share in gross tax revenue has stayed below 90% for six consecutive years, compared to consistently above 93% earlier.

States’ Demands

- 18 States including Odisha, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and Haryana demanded an increase in vertical devolution to 50% of the divisible pool.

- Several other States sought a moderate rise to 45–48%, citing rising fiscal pressures and shrinking revenues.

- Their demand was based on the fact that the share of divisible pool in gross tax revenue has fallen below 90% for six consecutive years, compared to consistently above 93% between FY13–FY18, due to the Centre’s growing reliance on cesses and surcharges.

Centre’s Position

- The Centre argued for “moderation in tax devolution”, opposing any increase beyond the current 41%.

- Cesses and surcharges are required for emergencies such as war, famine, or pandemics.

- Defence and infrastructure spending needs have expanded, requiring greater central resources.

- As per Finance Ministry data, collections from cesses rose from ₹44,688 crore in FY15 to ₹3.52 lakh crore in FY22, while surcharges increased from ₹15,702 crore in FY15 to ₹1.72 lakh crore (FY26 expected).

Commission’s Reasoning

- The Commission said putting a fixed limit on cesses and surcharges would be risky, though depending on them for too long is not good.

- It stated that States already have enough funds to carry out their constitutional duties.

- As a way forward, it suggested that the Centre should gradually move back to collecting more regular taxes instead of relying heavily on cesses and surcharges, so that the shareable pool of revenue becomes larger.

Key Concerns Raised

- Constitutional Intent: Did the framers anticipate such a disproportionate rise in non-shareable revenues?

- Mediator Role: By refusing to cap cesses, has the FC left States without safeguards against shrinking revenues?

- Efficiency Claim: The Centre’s claim of infrastructure efficiency overlooks the fact that high-performing States lose out under current distribution.

- Consensus Ignored: Nearly all States, cutting across political lines, demanded a larger share — yet the FC maintained status quo.

Conclusion

The real issue is not just the 41% rate but the shrinking divisible pool due to rising cesses and surcharges. Strengthening fiscal federalism requires expanding shareable revenues and balancing national priorities with State needs.

This topic is available in detail on our main website.