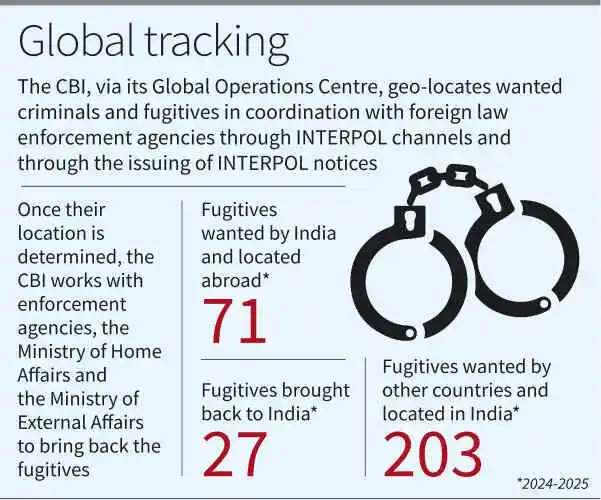

According to the DoPT Annual Report 2024–25, the CBI traced 71 fugitives abroad, the highest in the last 12 years. This marks a significant push in India’s extradition and international legal cooperation framework—an important GS Paper II & III theme for aspirants preparing through UPSC coaching in Hyderabad.

Who are Economic Offenders?

- People who commit financial crimes such as fraud, money laundering, tax evasion, bank scams, or wilful loan defaults.

- They often escape abroad to avoid facing trial or repaying debts in India.

- Their crimes usually involve large sums of public money and affect banks, investors, and the economy.

Why is it Difficult to Repatriate/Extradite Them?

- Legal Complexities: Extradition requires that the offence is recognized as a crime in both India and the foreign country.

- Limited Treaties: India has extradition treaties with only 48 countries and arrangements with 12 more. If the offender is in a country without a treaty, bringing them back becomes harder.

- Judicial Delays Abroad: Fugitives use appeals and human rights arguments (e.g., poor prison conditions in India) to delay extradition.

- Courts abroad carefully examine India’s legal and prison systems before approving extradition.

- Diplomatic Sensitivities: Extradition cases often depend on bilateral relations. Countries may hesitate if the case has political overtones.

Examples

- Vijay Mallya (UK): Accused of defaulting on loans worth ₹9,000+ crore; extradition approved but delayed due to appeals.

- The CBI Global Operations Centre works with foreign agencies and Interpol to locate and pursue fugitives.

Key Data (2024–25)

- 71 fugitives located abroad – highest since 2013.

- 27 fugitives returned to India during the year.

- Extradition treaties: India has agreements with 48 countries and arrangements with 12 more.

- Extradition requests (last 5 years): 137 sent; 134 accepted; 125 pending; 3 rejected.

- Successful extraditions: 25 fugitives brought back in five years.

- Letters Rogatory (judicial requests):

- 74 sent in 2024–25.

- 47 executed (42 by CBI, 5 by other agencies).

- 533 pending globally as of March 2025.

Challenges

- Slow extradition process: Many requests remain pending with foreign governments.

- Legal hurdles: Differences in judicial systems and evidentiary standards.

- Diplomatic sensitivities: Extradition often tied to bilateral relations.

- Funding and resources: Tracking fugitives abroad requires strong coordination and technology.

International Framework

- India is party to conventions like the UN Convention against Corruption, which provides a legal basis for cooperation.

- Interpol notices and global law enforcement networks are used to geo-locate fugitives.

Significance

- Rising numbers reflect India’s proactive stance in tracing fugitives.

- Successful returns reinforce rule of law and accountability.

- Underscores the need for faster judicial cooperation and sustained diplomacy—key takeaways for learners using UPSC online coaching.

CBI

Origin:

- Started as the Special Police Establishment (SPE) in 1941 to investigate corruption in wartime procurement.

- Later formalized under the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946.

Formation of CBI:

- In 1963, the Government of India set up the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) through a resolution of the Ministry of Home Affairs.

- It was created to expand the scope of SPE beyond corruption cases to include serious crimes.

Legal Basis:

- Though established by executive resolution, its powers come from the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946.

- This Act allows the CBI to investigate cases across India with the consent of State governments.

Parent Agency:

- Functions under the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions.

Santhanam Committee Recommendation:

- The Santhanam Committee on Prevention of Corruption (1962) recommended a central agency to tackle corruption and serious crimes, leading to the creation of CBI.

Headquarters: Located in New Delhi.

Conclusion

The record number of fugitives traced abroad in 2024–25 reflects India’s growing global coordination against crime. However, delays in extradition and pending judicial requests underline the need for legal reforms, and sustained diplomatic pressure to ensure fugitives face justice in India.

This topic is available in detail on our main website.